Art Freed Show in New York City in the 60s

| Alan Freed | |

|---|---|

Freed c. 1958 | |

| Born | Albert James Freed (1921-12-xv)Dec fifteen, 1921 Windber, Pennsylvania, U.Southward. |

| Died | Jan 20, 1965(1965-01-20) (anile 43) Palm Springs, California, U.S. |

| Resting place | Lake View Cemetery, Cleveland, Ohio, U.S. |

| Occupation | Disc jockey |

| Years active | 1945–65 |

| Spouse(s) |

|

| Children | 4 |

Albert James "Alan" Freed (December 15, 1921 – January 20, 1965) was an American disc jockey.[1] He also produced and promoted large traveling concerts with various acts, helping to spread the importance of rock and roll music throughout North America.

In 1986, Freed was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. His "role in breaking down racial barriers in U.S. popular culture in the 1950s, by leading white and black kids to listen to the same music, put the radio personality 'at the vanguard' and made him 'a really important effigy'", co-ordinate to the Executive Director.[ii]

Freed was honored with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame in 1991. The organization'southward website posted this note: "He became internationally known for promoting African-American rhythm and blues music on the radio in the United States and Europe under the name of rock and roll".[3]

In the early on 1960s, Freed'south career was destroyed by the payola scandal that hit the broadcasting industry, as well as by allegations of taking credit for songs he did not write[4] and past his chronic alcoholism.[5]

Early on years [edit]

Freed was born to a Russian Jewish immigrant male parent, Charles S. Freed, and Welsh-American female parent, Maude Palmer, in Windber, Pennsylvania. In 1933, Freed's family moved to Salem, Ohio, where Freed attended Salem High School, graduating in 1940. While Freed was in high school, he formed a band called the Sultans of Swing in which he played the trombone. Freed's initial ambition was to exist a bandleader; however, an ear infection put an end to that dream.[ citation needed ]

While attending Ohio Land University, Freed became interested in radio. Freed served in the U.s. Ground forces during World War Two and worked equally a DJ on Armed Forces Radio. Shortly afterward Earth War II, Freed landed dissemination jobs at smaller radio stations, including WKST (New Castle, Pennsylvania); WKBN (Youngstown, Ohio); and WAKR (Akron, Ohio), where, in 1945, he became a local favorite for playing hot jazz and pop recordings. Freed enjoyed listening to these new styles because he liked the rhythms and tunes.

Career [edit]

Freed was the commencement radio disc jockey and concert producer who often played and promoted rock and gyre; he popularized the phrase "rock and roll" on mainstream radio[six] in the early on 1950s. (The term already existed, and had been used by Billboard as early as 1946, but it remained obscure.)[7]

Several sources suggest that he first discovered the term (as a euphemism for sexual intercourse) on the record "Lx Infinitesimal Man" past Billy Ward and his Dominoes.[eight] [9] The lyrics include the line, "I rock 'em, roll 'em all dark long",[ten] however, Freed did non accept that inspiration (or that meaning of the expression) in interviews, and explained his view of the term as follows: "Rock 'n curl is actually swing with a modern name. It began on the levees and plantations, took in folk songs, and features dejection and rhythm".[xi]

He helped bridge the gap of segregation among young teenage Americans, presenting music by black artists (rather than encompass versions past white artists) on his radio plan, and arranging live concerts attended past racially mixed audiences.[12] Freed appeared in several motility pictures as himself. In the 1956 movie Rock, Rock, Stone, Freed tells the audience that "rock and whorl is a river of music which has absorbed many streams: rhythm and blues, jazz, ragtime, cowboy songs, state songs, folk songs. All take contributed profoundly to the big shell."[13]

WAKR Akron [edit]

In June 1945, Alan Freed joined WAKR (1590 AM) in Akron, Ohio and quickly became a star journalist.[14] Dubbed "The Old Knucklehead",[15] Freed had up to five hours of airtime every day on the station by June 1948:[xvi] the daytime Jukebox Serenade, the early on-evening Wax Works and the nightly Asking Review.[17] [18] Freed also had brief run-ins with management and was at one bespeak temporarily fired for violating studio rules[19] and failing to show up for piece of work for several days in a row.[20]

At the pinnacle of his popularity in 1948, Freed signed a contract extension with WAKR that included a non-compete clause inserted by possessor S. Bernard Berk, preventing Freed from working at whatsoever station within a radius of 75 miles (121 kilometers) of Akron for a full year.[20] Freed left WAKR on February 12, 1950 and after ane programme on competing station WADC (1350 AM) several days later, Berk and WAKR sued Freed to enforce the clause.[21] Freed repeatedly lost in court, even after appealing his case to the Supreme Courtroom of Ohio;[22] Berk's successful implementation of the non-compete is at present recognized within the manufacture as a model for broadcasters regarding on-air talent contracts.[20]

WJW Cleveland [edit]

In the tardily 1940s, while working at WAKR, Freed met Cleveland record shop owner Leo Mintz. Tape Rendezvous, 1 of Cleveland'due south largest record stores, had begun selling rhythm and blues records. Mintz told Freed that he had noticed increased interest in the records at his store, and encouraged him to play them on the radio.[23] [24] In 1951, having already joined goggle box station WXEL (aqueduct 9, now WJW aqueduct 8) in the centre of 1950 equally an announcer, Freed moved to Cleveland, which at 39 miles from Akron was within the range of the still in force not-compete clause.[25] Even so, in April, through the help of William Shipley, RCA'south Northern Ohio benefactor, he was released from the not-compete clause. He was then hired by WJW radio for a midnight plan sponsored by Main Line, the RCA Benefactor, and Record Rendezvous. Freed peppered his spoken communication with hipster linguistic communication, and, with a rhythm and blues record called "Moondog" as his theme song, broadcast R&B hits into the night.[ commendation needed ]

Mintz proposed ownership airtime on Cleveland radio station WJW (850 AM), which would be devoted entirely to R&B recordings, with Freed equally host.[23] On July 11, 1951, Freed began playing rhythm and blues records on WJW.[26] While R&B records were played for many years on lower-powered, inner urban center radio stations aimed at African-Americans, this is arguably the first fourth dimension that authentic R&B was featured regularly on a major, mass audience station. Freed called his evidence "The Moondog Firm" and billed himself as "The King of the Moondoggers". He had been inspired by an instrumental slice chosen "Moondog Symphony" that had been recorded by New York-based composer and street musician Louis T. Hardin, known professionally as Moondog. Freed adopted the record as his show'south theme music. His on-air mode was energetic, in dissimilarity to many contemporary radio presenters of traditional pop music, who tended to sound more subdued and low-fundamental in manner. He addressed his listeners as if they were all office of a brand-believe kingdom of hipsters, united in their dearest for blackness music.[26] He also began popularizing the phrase "rock and ringlet" to describe the music he played.[27]

Concert poster for the Coronation Ball

Later on that year, Freed promoted dances and concerts featuring the music he was playing on the radio. He was ane of the organizers of a five-act show called "The Moondog Coronation Brawl" on March 21, 1952, at the Cleveland Arena.[28] This event is now considered to have been the showtime major stone and ringlet concert.[4] Crowds attended in numbers far beyond the arena's chapters, and the concert was shut down early due to overcrowding and a near-riot.[28] Freed gained notoriety from the incident. WJW immediately increased the airtime allotted to Freed's program, and his popularity soared.[26]

In those days, Cleveland was considered by the music industry to be a "breakout" urban center, where national trends first appeared in a regional market place. Freed's popularity made the pop music business have observe. Soon, tapes of Freed's programme, Moondog, began to air in the New York Urban center area over station WNJR 1430 (now WNSW), in Newark, New Bailiwick of jersey.[26] [29]

New York stations [edit]

In July 1954, following his success on the air in Cleveland, Freed moved to WINS (1010 AM) in New York City. Hardin, the original Moondog, later took a court action suit confronting WINS for damages against Freed for infringement in 1956, arguing prior claim to the name "Moondog", under which he had been composing since 1947. Hardin nerveless a $6,000 judgment from Freed, also as an agreement to give up further usage of the name Moondog.[30] Freed left the station in May 1958 "subsequently a riot at a dance in Boston featuring Jerry Lee Lewis".[31] WINS somewhen became an effectually-the-clock Elevation 40 rock and gyre radio station, and would remain and then until April 19, 1965, long later Freed left and 3 months after he had died—when it became an all-news outlet.

Before, in 1955 and 1956, Freed had hosted "The Camel Rock and Roll Trip the light fantastic toe Party", so named for the sponsor Camel cigarettes. The half hour program headlined Count Basie and his Orchestra and later Sam The Homo Taylor and His Orchestra, and featured weekly rock due north roll guests such equally LaVern Baker, Clyde McPhatter and Frankie Lyman and the Teenagers.[32] The radio program was also referred to as "Alan Freed'due south Stone 'n' Whorl Dance Party"[33] on CBS Radio from New York.[34] [35]

Freed also worked at WABC (AM) starting in May 1958 but was fired from that station on November 21, 1959[36] after refusing to sign a argument for the FCC that he had never accepted payola bribes.[31]

He afterwards arrived at a small Los Angeles station, KDAY (1580 AM) and worked in that location for most 1 twelvemonth.[37]

Picture and tv [edit]

Freed as well appeared in a number of pioneering stone and roll movement pictures during this period. These films were oftentimes welcomed with tremendous enthusiasm by teenagers considering they brought visual depictions of their favorite American acts to the big screen, years before music videos would present the aforementioned sort of image on the minor telly screen.

Freed appeared in several move pictures that presented many of the large musical acts of his day, including:

- 1956: Rock Around the Clock featuring Freed, Bill Haley & His Comets, The Platters, Freddie Bong and the Bellboys, Lisa Gaye.

- 1956: Rock, Rock, Rock [38] featuring Freed, Teddy Randazzo, Tuesday Weld, Chuck Berry, Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, Johnny Burnette, LaVern Baker, The Flamingos, The Moonglows.

- 1957: Mister Stone and Roll featuring Freed, Rocky Graziano and Teddy Randazzo, Lionel Hampton, Ferlin Croaking, Frankie Lymon, Little Richard, Brook Benton, Chuck Drupe, Clyde McPhatter, LaVern Bakery, Screamin' Jay Hawkins.

- 1957: Don't Knock the Stone featuring Freed, Beak Haley and His Comets, Alan Dale, Little Richard and the Upsetters, The Treniers, Dave Appell and His Applejacks.

- 1959: Become, Johnny Become! featuring Freed, Jimmy Clanton, Chuck Berry, Ritchie Valens, Eddie Cochran, The Flamingos, Jackie Wilson, The Cadillacs, Sandy Stewart, Jo Ann Campbell, Harvey Fuqua and The Moonglows. Chuck Berry also played Freed'south pal and sidekick, a groundbreaking role in those days.

Freed was given a weekly primetime Idiot box series, The Large Beat, which premiered on ABC on July 12, 1957.[39] The show was scheduled for a summer run, with the agreement that if there were enough viewers, information technology would continue into the 1957–58 television flavor. Although the ratings for the show were strong, it was suddenly terminated. The Wall Street Journal summarized the end of the program as follows. "Four episodes into "The Big Beat," Freed'southward prime number-time Tv set music series on ABC, an uproar was caused when African-American artist Frankie Lymon was seen on Television receiver dancing with a white audience fellow member". Two more episodes were aired[40] merely the show was suddenly cancelled.[41] Some sources indicate that the cancellation was triggered by an uproar amidst ABC's local affiliates in the S.[42] [43]

During this period, Freed was seen on other pop programs of the twenty-four hours, including To Tell the Truth, where he is seen defending the new "rock and whorl" sound to the panelists, who were all clearly more comfortable with swing music: Polly Bergen, Ralph Bellamy, Hy Gardner and Kitty Carlisle.

Legal problem, payola scandal [edit]

In 1958, Freed faced controversy in Boston when he told the audience, "It looks like the Boston police force don't want you to accept a skilful time." Equally a effect, Freed was arrested and charged with inciting to anarchism, and was fired from his task at WINS.[44]

Freed's career was significantly affected when it was shown that he had accepted payola (payments from tape companies to play specific records), a practice that was highly controversial at the time. He initially denied taking payola[45] merely later admitted to his fans that he had accustomed bribes.[46] Freed refused to sign a argument for the FCC while working at WABC (AM) to state that he never received bribes.[31] That led to his termination.[47] [36]

In 1960, payola was made illegal. In December 1962, later beingness charged on multiple counts of commercial bribery, Freed pled guilty to two counts of commercial blackmail and was fined three hundred dollars and given a suspended sentence.[48] [49]

There was too a series of disharmonize of interest allegations, that he had taken songwriting co-credits that he did not deserve.[4] The most notable example was Chuck Drupe's "Maybellene". Taking partial credit allowed him to receive part of a song'due south royalties, which he could help increase past heavily promoting the record on his ain program. (Berry was somewhen able to regain the writing credit.) In another example, Harvey Fuqua of The Moonglows insisted Freed's name was not merely a credit on the song "Sincerely" and that he did actually co-write it (which would still be a conflict of interest for Freed to promote). Another grouping, The Flamingos also claimed that Freed had wrongly taken writing credit for some of their songs.[50]

In 1964 Freed was indicted past a federal grand jury for taxation evasion and ordered to pay $37,920 in taxes on income he had allegedly non reported. Most of that income was said to exist from payola sources.[51]

Personal life [edit]

On August 22, 1943, Freed married first wife, Betty Lou Bean. They had ii children, daughter Alana (deceased) and son Lance. They divorced on December 2, 1949. On August 12, 1950, Freed married Marjorie J. Hess. They besides had two children, daughter Sieglinde and son Alan Freed, Jr. They divorced on July 25, 1958. On August viii, 1958, Freed married Inga Lil Boling with whom he had no children. They remained together until his death.[52]

Afterward years and decease [edit]

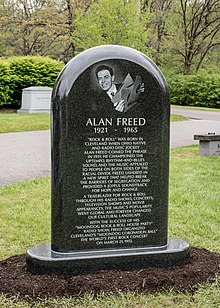

Freed'due south gravestone in Cleveland

Because of the negative publicity from the payola scandal, no prestigious station would employ Freed, and he moved to the W Declension in 1960, where he worked at KDAY/1580 in Santa Monica, California.[37] In 1962, after KDAY refused to let him to promote "rock and roll" stage shows, Freed moved to WQAM in Miami, Florida, arriving in August 1962.[53] Recognizing that his career in major markets might be over, his alcohol consumption increased and the job lasted only two months.[54]

During 1964, he returned to the Los Angeles area for a short stint at the Long Beach station KNOB/97.9.[55] [56] [57]

Living in the Racquet Gild Estates neighborhood of Palm Springs, California,[58] Freed died on January 20, 1965, from uremia and cirrhosis brought on by alcoholism, at the historic period of 43. Prior to his death, the FBI had continued to maintain that he owed $38,000 for taxation evasion, simply Freed did not have the financial means to pay that amount.[48]

He was initially interred in the Ferncliff Cemetery in Hartsdale, New York.[59] In March 2002, Judith Fisher Freed, his daughter-in-constabulary, carried his ashes to the Stone and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio.[60] On August 1, 2014, the Hall of Fame asked Alan Freed'southward son, Lance Freed, to remove the ashes permanently, which he did.[61] The Freed family afterward interred his ashes at Cleveland's Lake View Cemetery beneath a jukebox-shaped memorial featuring Freed's image.[62]

In the popular media [edit]

An archived sample of Freed's introduction on the Moondog Bear witness was used by Ian Hunter in the opening of the song "Cleveland Rocks", from Hunter's 1979 album Yous're Never Alone with a Schizophrenic.

The 1978 motility picture American Hot Wax was inspired by Freed's contribution to the rock and roll scene. Although director Floyd Mutrux created a fictionalized account of Freed'due south terminal days in New York radio by using real-life elements outside of their actual chronology, the moving picture does accurately convey the fond relationship between Freed, the musicians he promoted, and the audiences who listened to them. The moving-picture show starred Tim McIntire equally Freed and included cameo appearances by Chuck Berry, Screamin' Jay Hawkins, Frankie Ford and Jerry Lee Lewis, performing in the recording studio and concert sequences.

On January 23, 1986, Freed was role of the first group inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland.[63] In 1988, he was also posthumously inducted into the National Radio Hall of Fame.[64] On December 10, 1991, Freed was given a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame.[65] The VH1 series Behind The Music produced an episode on Freed featuring Roger Steffens. In 1998, The Official Website of Alan Freed went online with the jumpstart from Brian Levant and Michael Ochs archives as well every bit a home page biography written past Ben Fong-Torres. On February 26, 2002, Freed was honored at the Grammy Awards with the Trustees Accolade. In 2017 he was inducted into the National Rhythm & Blues Hall of Fame in Detroit, Michigan.

Freed was used as a grapheme in Stephen King's short story, "Yous Know They Got a Hell of a Band",[66] and was portrayed by Mitchell Butel in its television adaptation for the Nightmares & Dreamscapes mini-serial.[ citation needed ] He was the subject of a 1999 television motion-picture show, Mr. Stone 'n' Coil: The Alan Freed Story, starring Judd Nelson and directed by Andy Wolk.[67] The 1997 film Telling Lies in America stars Kevin Bacon equally a disc jockey with a loose resemblance to Freed.[68] Jack Macbrayer portrayed Freed on the Comedy Central show Drunk History in a segment on Freed's legacy. The Cleveland Cavaliers' mascot Moondog is named in honor of Freed.[66]

Freed is mentioned in The Ramones' song "Do You Remember Rock 'northward' Gyre Radio?" as one of the band's idols.[66] Other songs that reference Freed include "The King of Rock 'n Roll" by Terry Cashman and Tommy West, "Ballrooms of Mars" by Marc Bolan, "They Used to Call it Dope" past Public Enemy, "Payola Blues" by Neil Young, "Done Too Soon" by Neil Diamond, "The Ballad of Dick Clark" by Skip Battin, a fellow member of the Byrds, and "This Is Not Goodbye, Simply Goodnight" by Kill Your Idols.

Legacy [edit]

Freed'southward importance to the musical genre is confirmed by his induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and his 1991 star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. The DJ was as well inducted into the Radio Hall of Fame in 1988. The organization'southward Web page states that "despite his personal tragedies, Freed'due south innovations helped make rock and ringlet and the Top-40 format permanent fixtures of radio".[69]

The Wall Street Periodical in 2015 recalled "Freed's sizable contributions to rock 'north' gyre and to teenagers' more than tolerant view of integration in the 1950s". The publication praised the help he gave to "hundreds of blackness and white artists" and said that "his tireless efforts helped create thousands of jobs for studio musicians, engineers, record producers, concert promoters and musical instrument manufacturers".[70]

One source said that "No man had as much influence on the coming culture of our society in such a brusque menses of time equally Alan Freed, the real King of Rock n Roll".[71] Another source summarized his contribution every bit follows:[72]

Alan Freed has secured a place in American music history every bit the first important rock 'due north' curl disc jockey. His ability to tap into and promote the emerging blackness musical styles of the 1950s to a white mainstream audition is seen as a vital step in rock's increasing potency over American culture.

References [edit]

Citations [edit]

- ^ Obituary Diverseness, Jan 27, 1965, folio 54.

- ^ "Stone and Coil Hall of Fame ousts DJ Alan Freed'due south ashes, adds Beyonce's leotards". CNN. Baronial iv, 2014. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ "ALAN FREED". Walk of Fame. May 27, 1991. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Son of DJ Alan Freed says Rock Hall of Fame no longer want his cremated remains". The Guardian. August 5, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "The Human being Who Knew It Wasn't But Rock 'due north' Gyre". The New York Times. October 14, 1999. Retrieved Feb 3, 2021.

He began drinking heavily ... he was accused of taking lucrative songwriting credits for songs that were actually written by members of the immature groups he championed.

- ^ "Alan Freed". Britannica. March 4, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

Alan Freed did non coin the phrase rock and curl; however, by way of his radio bear witness, he popularized information technology and redefined information technology. One time slang for sex, it came to mean a new form of music. This music had been around for several years, but…

- ^ Billboard 22 Jun 1946. Billboard. June 24, 1946. p. 33.

- ^ "Alan Freed". History of Rock. January 4, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

- ^ "Ch. 3 "Rockin' Around The Clock"". Michigan Stone n Ringlet Legends. June 22, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2021.

By the middle of the 20th century, the phrase "rocking and rolling" was slang for sex in the black community just Freed liked the sound of it and felt the words could be used differently.

- ^ Ennis, Philip (May ix, 2012). The History of American Pop. Greenhaven Publishing LLC. p. 18. ISBN978-1420506723.

- ^ "Alan Freed Dies". Ultimate Classic Stone. January 15, 2015. Retrieved Jan 28, 2021.

- ^ Larkin, Colin. "Freed, Alan". Encyclopedia of Popular Music (4th ed.).

- ^ James, p. 59.

- ^ Price, Mark J. (November 14, 2016). "Local history: Earlier they were stars, they were ours". Akron Beacon Periodical. Black Press. Retrieved February 8, 2020.

- ^ Freed, Alan (November two, 1947). "A Personal Bulletin From Alan Freed (Advertisement)". Akron Beacon Journal. Knight Newspapers. p. 11B. Retrieved February ix, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Whiteman Off, Freed On Again". Akron Beacon Journal. Knight Newspapers. June 30, 1948. p. xx. Retrieved February seven, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Offineer, Bee (January 16, 1946). "Freed Sings And Fans Write". Akron Beacon Journal. Knight Newspapers. p. 4. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Offineer, Bee (July 23, 1947). "Freed Premiers 'Wax Works'". Akron Buoy Journal. Knight Newspapers. p. 7. Retrieved May 22, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Stopher, Robert H.; Jackson, James S. (February viii, 1948). "Behind The Front Page: Miscellany". Akron Buoy Journal. Knight Newspapers. p. 2B. Retrieved May 23, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ a b c Dyer, Bob (October 14, 1990). "Contract clause led to Freed's fame". Akron Buoy Periodical. Knight Ridder. pp. F1, F6. Retrieved Feb nine, 2020 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Akron Jockey, WAKR Tangle" (PDF). The Billboard. Vol. 62, no. 8. The Billboard Publishing Company. Feb 25, 1950. p. sixteen. Retrieved Jan 31, 2020 – via American Radio History.

- ^ "Court Slaps Ban On Alan Freed In Jockey Fight" (PDF). The Billboard. Vol. 62, no. ix. The Billboard Publishing Company. March 4, 1950. p. 20. Retrieved January 31, 2020 – via American Radio History.

- ^ a b "Encyclopedia of Cleveland History, Rock'n'Roll". Ech.cwru.edu . Retrieved November 6, 2014.

- ^ Jackson, p. 35.

- ^ Denny, Frank (September 30, 1950). "D. J.south must change for TV, says Freed" (PDF). TV Today. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 28, 2020. Retrieved January 28, 2020 – via AlanFreed.com.

- ^ a b c d Miller, pp. 57–61.

- ^ Bordowitz, p. 63.

- ^ a b Sheerin, Jude (March 21, 2012). "How the world'southward first stone concert ended in chaos". BBC News . Retrieved March 12, 2014.

- ^ "'Moondog' Alan Freed dead at 43: Life Stories Revisited". Cleveland Plain Dealer. Jan twenty, 2011.

- ^ Scotto, Robert (2007). Moondog, The Viking of sixth Avenue: The Authorized Biography Procedure Music edition ISBN 0-9760822-8-iv, 978-0-9760822-eight-half-dozen (Preface past Philip Glass)

- ^ a b c "Freed, Alan". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. December ii, 2017. Retrieved February iv, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Freed'south Rock 'N' Scroll Dance Political party .. Episodic log".

- ^ "The Alan Freed Collection 1956 (LP Side 1)". Youtube. Archived from the original on December eleven, 2021. Retrieved August 7, 2020.

- ^ "RadioEchoes.com". Radioechoes.com . Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ "Rhino Factoids: Alan Freed's Rock 'n' Roll Dance Party | Rhino". Rhino.com . Retrieved October 11, 2019.

- ^ a b Curtis, p. 37.

- ^ a b "Radio: How a disgraced DJ fabricated his way to KDAY". LA Daily News. December 23, 2019. Retrieved Feb four, 2021.

Small. Daytime-only at the time. Though information technology did have Art Laboe and l,000 watts, and then it wasn't all bad.

- ^ "Alan Freed and His Rock and Roll Band – Rock and Scroll Boogie (from the movie Rock Rock Rock – 1956)". YouTube. Retrieved May 31, 2021.

- ^ Brooks & Marsh, p. 136.

- ^ Sagolla, Lisa Jo (September 12, 2011). Stone 'due north' Gyre Dances of the 1950s. Performing Arts. p. 74. ISBN978-0313365560.

- ^ "Moondog'south Final Sign Off". WSJ. Jan twenty, 2021. Retrieved February iv, 2021.

- ^ Jackson, p. 168.

- ^ "How the globe's first stone concert ended in anarchy". BBC News. March 21, 2012. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Guralnick, p. 235.

- ^ "ALAN FREED IS OUT IN 'PAYOLA' STUDY; Deejay Jockey Refuses to Sign WABC Deprival on Principle – Says He Took No Bribes". New York Times. November 22, 1959. Retrieved Feb four, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Freed". Ohio Central History. March 17, 1964. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Radio: How a disgraced DJ made his way to KDAY". LA Daily News. December 23, 2019. Retrieved February four, 2021.

- ^ a b "Alan Freed". Rockabilly Hall of Fame. June 10, 2016. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Nov 21, 1959: Alan Freed, Originator of the Term "Rock and Roll" is Fired from His Chore equally a DJ!". History and Headline. November 21, 2014. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Freed". New York Times. October fourteen, 1999. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

Mr. Jackson, who wrote the Freed biography, said that 2 members of the virtuoso group the Moonglows told him that Mr. Freed had no interest with their large hit Sincerely yet took a writing credit for it and received the royalties. Maybellene .... Mr. Berry went to court eventually and succeeded in having Mr. Freed's proper name removed as co-writer.

- ^ "Alan Freed". New York Times. March 17, 1964. Retrieved February iii, 2021.

- ^ Jackson, p. 214.

- ^ "Alan Freed to Play Disks On Miami Station WQAM". New York Times. August 29, 1962. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Alan Freed". Rockabilly Hall of Fame. September 27, 1991. Retrieved January 27, 2021.

- ^ Los Angeles Radio People, Where are They Now? – F, retrieved March 6, 2012.

- ^ AlanFreed.Com: expiry document, Alanfreed.com, retrieved March half-dozen, 2012.

- ^ "Alan Freed". Reel Radio. November 27, 1991. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ Meeks, Eric Grand. (2014) [2012]. The Best Guide Ever to Palm Springs Celebrity Homes. Horatio Limburger Oglethorpe. pp. 41–43. ISBN978-1479328598.

- ^ McCarty, James F.; Dealer, The Plain (March i, 2016). "Alan Freed's ashes, evicted from Rock Hall, have a final resting place of prominence in Cleveland". cleveland.

- ^ Vigil, Vicki Blum (2007). Cemeteries of Northeast Ohio: Stones, Symbols & Stories. Cleveland, OH: Grey & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59851-025-6

- ^ Alan Duke (Baronial iii, 2014). "Stone and Whorl Hall of Fame to remove Alan Freed's ashes". CNN . Retrieved Nov vi, 2014.

- ^ Feran, Tom (May 8, 2016). "Alan Freed, 'begetter of rock,' gets a memorial in stone". The Evidently Dealer . Retrieved January 1, 2020.

- ^ "Alan Freed – 1986 – Category:Not-Performer". Stone & Roll Hall of Fame. 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ "Alan Freed". National Radio Hall Of Fame. 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ "Alan Freed". Walkoffame.com. Hollywood Chamber of Commerce. 2017. Retrieved January 5, 2017.

- ^ a b c Danesi, p. 121.

- ^ Weinraub, Bernard (Oct fourteen, 1999). "The Man Who Knew It Wasn't Only Rock 'n' Roll". The New York Times . Retrieved Jan v, 2017.

- ^ Holden, Stephen (October 9, 1997). "lx'due south Payola Is His First Taste of America". The New York Times . Retrieved January v, 2017.

- ^ "ALAN FREED". Radio Hall of Fame. January 20, 1989. Retrieved February 4, 2021.

- ^ "Moondog's Last Sign Off". WSJ. January xix, 2015. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

- ^ "Alan Freed: More than Than Just The Human being Who Named Rock Northward Ringlet". Seniors' Lifestyle. February vii, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

- ^ "Freed, Alan 'Moondog' (1921–1965)". encyclopedia.com. January eleven, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2021.

Full general bibliography [edit]

- Bordowitz, Hank (2004). Turning Points in Rock and Roll . New York: Citadel Printing. ISBN978-0-8065-2631-7.

- Brooks, Tim; Marsh, Earle F. (2009). The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows, 1946–Nowadays. Random House. ISBN978-0307483201.

- Curtis, James M. (1987). Rock Eras: Interpretations of Music and Lodge, 1954–1984 . Popular Press. ISBN978-0-87972-369-9 . Retrieved November xx, 2011.

- Danesi, Marcel (2016). Concise Dictionary of Popular Culture. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN978-1442253124.

- Guralnick, Peter (2005). Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN0-316-37794-v.

- Jackson, John A. (1991). Big Beat Heat: Alan Freed and the Early Years of Rock & Roll. Schirmer. ISBN0-02-871155-6.

- James, David E. (2015). Stone 'N' Picture: Cinema'south Dance with Popular Music. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0199387625.

- Miller, James (1999). Flowers in the Dustbin: The Rising of Rock and Roll, 1947–1977. Simon & Schuster. ISBN0-684-80873-0.

Further reading [edit]

- Dawson, Jim (2005) [1989]. Rock Around the Clock: The Tape That Started the Rock Revolution. Backbeat Books/Hal Leonard. ISBN 0-87930-829-X.

- Smith, Wes (Robert Weston). The Pied Pipers of Stone and Roll: Radio Deejays of the 50s and 60s. Longstreet Press. ISBN 0-929264-69-X.

- Wolff, Carlo (2006). Cleveland Rock and Roll Memories. Cleveland: Gray & Company, Publishers. ISBN 978-1-886228-99-3.

External links [edit]

- Official website

- DVD review of Mr. Rock 'due north Coil

- The Alan Freed Tribute Page

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alan_Freed

0 Response to "Art Freed Show in New York City in the 60s"

Post a Comment